Here are some of the insights we can take away from Julia’s experience.

Criminal gangs prey on people’s vulnerabilities

At the beginning of the podcast, we hear how Julia came from a poor family in her village and growing up she had no access to the internet, TV or the outside world.

Julia knows she’s smart and wants a better life. She falls in love with a man, marries him a few months later and they both move to Kyiv. Unfortunately, he turns out to be unreliable and Julia ends up back home in her village with her young daughter, Marta.

For a while she ends up travelling to Poland every few months for work but no matter how hard she works it’s never enough. Her mother then gets sick and Julia has medical bills to pay on top of everything else. She goes to Poland one more time but can no longer afford to wait at home for another six months.

Then a woman in her village says she can help and gives Julia the number of some people who can help her get work abroad.

Human trafficking is a well-oiled business model for criminal gangs

When Julia leaves her village with the gang, she is unaware that she is being illegally trafficked, nor does she know that she will be taken across the Channel to the UK.

Julia is taken to a strange house in a country she doesn’t know and where she doesn’t speak the language. The gang take her passport and give her fake documents and a national insurance number.

At first she is given work in a fancy hotel managed by a Ukrainian woman in West London. After two weeks of back-breaking work, Julia only receives £90 in wages. After speaking with another Ukrainian girl who cleans with her, Julia learns that the Ukrainian woman managing the hotel is working with the trafficking gang and is receiving a cut of Julia’s salary.

Julia, like many victims of modern slavery, finds herself trapped without money, passport, legal status or a way home. The gang controls where she lives, how much rent she pays, where she works and they dictate the amount of debt she owes. Despite sleeping on a broken airbed with bed bugs, Julia is told she owes the gang £4,500 – an unimaginable level of debt. This means she cannot send money back home for her daughter.

Sex trafficking is the most lucrative of all forms of modern slavery

Desperate to pay off her debt, Julia looks for work elsewhere but is told that her documents are fake and is refused. She then sees an ad in Polish for escort services and that no documents are required. Julia does not want to do this but with her debt accumulating she felt she had no choice but to respond.

At first, Julia makes some money and is able to send back £100 to her daughter Marta. However, she is then told she has to pay £4,000 for her profile on the escort website on top of the £4,000 she owes to the gang who trafficked her.

Julia has no control over who she sees or what she’ll do. Often the brothel’s receptionists promise clients that Julia will perform sexual acts she has not agreed to do. If she refuses to do something, she has to pay back her money. On a given day Julia would see 16 clients but only earn £90.

Sex trafficking is by far the most lucrative of all forms of trafficking – and it is untaxed. Police believe that some organised criminal gangs running brothels in the UK can make a profit of over £1million each week. As we learn from the trial of Julia’s traffickers, one victim would earn £200,000 for the traffickers in a year and there were four or five people in each brothel. A gang may control 20-25 brothels in one town.

Modern slavery doesn’t look like what you expect

Victims are controlled by invisible chains of coercion and deception. Debt and fear of what might happen if they didn’t pay it back was the main psychological weapon of control. Julia said that many of the girls took drugs to help them deal with the trauma.

Many of the women who spoke with Annie Kelly during her years of reporting modern slavery said that they clung to the fact they kept some of the money they earnt and were able to send it back to their families.

It is also hidden in plain sight. Brothels can be found in high streets, nice massage parlours, in beautiful detached homes in nice neighbourhoods, AirBnbs, hotels and literally anywhere you can use a fake name.

Comprehensive support was essential for Julia’s recovery

Julia is alone at a brothel in Sunbury-upon-Thames when she is discovered by Surrey Police during a raid. Although initially distrustful of the police, Julia agrees to go into the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) where she is matched with Sarah, a Victim Support Navigator from Justice and Care.

There are very few Victim Navigators in the UK and the role has only existed for a few years. Part of Sarah’s role is accompanying police on raids so that she is the first person to speak with victims. There can be an uncomfortable power dynamic between police and victims and the onus is on the victims to say something.

When Julia first met Sarah she was nervous, reserved and closed off to receiving support and counselling. She needed a period of stability and distance from the situation she had just fled and Sarah’s role was to be there for her when she needed.

Victim support is essential for giving survivors the strength to help the police. Justice and Care says that 92% of victims matched with a navigator decide to help the police to try to bring their traffickers to justice. Julia says that without a victim navigator like Sarah she would have never made it trial.

It is hard to prosecute traffickers

Remarkably Julia decided to work with the police to bring her traffickers to justice. The operation into the criminal gang picked apart a complex web of sexual exploitation, money laundering and fraud. The tentacles of the criminal operation stretched from the UK into Poland with most of the money being siphoned off to a big boss over there who was really running the show. With the police in Poland, Surrey Police were able to identify 127 women of interest, some that were easy to find, some they knew of but couldn’t locate and others they couldn’t identify. Not all the women identified wanted to go to court but they were more likely to when they heard that Julia would also be testifying.

The Modern Slavery Act increased the support and protection given to victims of modern slavery and for the first time introduced the possibility of a life sentence for traffickers. However these are some of the most difficult charges to get to court. The investigations are complex, expensive and because it’s hard to get evidence that proves trafficking, a conviction relies on a victim staying with the process, often for years. In 2021, the year Julia went to court, only 114 people were convicted under the Modern Slavery Act. Since the legislation came into effect in 2015, not one person has received a life sentence and the average sentence for convicted traffickers is three to seven years.

Experts believe that the crime is not understood enough by courts, judges, juries and many police forces across the country. It’s often far easier for Crown Prosecution Services to charge under other crimes such as controlling prostitution for gain as this is far easier to prove and they are more likely to get a conviction.

In Julia’s trial, two receptionists were sentenced to 15 and 20 months suspended, Marek who collected the money received 32 months and Alexander received three and half years.

Survivors are still at risk

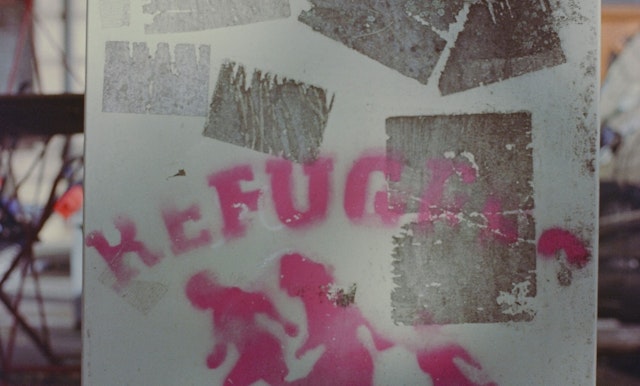

In the final episode, we hear that although Julia is recognised as a trafficking victim, it isn’t guaranteed the Home Office will allow her to stay in the UK as a refugee. Being a victim of trafficking or assisting the police in a trial does not guarantee asylum in the UK. Home Office date from 2016-2021 shows 6,066 victims of trafficking requested leave to remain in the UK but only 447 (just 7%) were allowed to stay.

At the same time Julia is scared to go home – the traffickers know where her family lives and she is convinced they will come after her and her daughter if she returns. People who have been trafficked are more vulnerable to being exploited again once they return to their home countries.

To listen to the podcast, go to The Guardian or Apple or Spotify or wherever you usually get your podcasts!